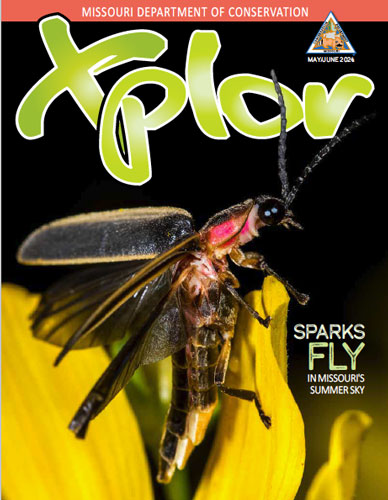

Fireflies — also known as lightning bugs — are neither flies nor bugs. They’re beetles. The next time you catch one, take a look at its wings. Like all beetles, a firefly’s front wings — called elytra (el-ih-trah) — are thick and leathery, and they form a straight line where they meet on the back. When a firefly wants to fly, it holds its elytra out of the way and flaps its delicate back wings. When it wants to rest, it folds its elytra over its back wings to protect them.

More than 2,000 kinds of these blinky beetles wink worldwide. They’re found on every continent except Antarctica. Over 170 species live in the United States and Canada. About two dozen show up in the Show-Me State, and we may have even more. Some species look alike, and even experts have trouble telling them apart.

Escargot, Anyone?

In late summer, mama fireflies lay dozens of tiny eggs in soggy soil, rotting wood, or under leaf litter. In two or three weeks, the eggs split open and out pop wiggly, wingless larvae that glow in the dark.

The little lightning bugs don’t glow to show off. The gleam is a warning to would-be predators that these beetle babies taste bad! If a bird eats one and gets sick, the glow helps it remember not to gulp down anything else that glows.

Glowworms are vicious predators, and their favorite foods are something the French call escargot (ess-car-go). You, however, probably call them snails. Glowworms find meals by following slime trails left by snails and slugs. Once they locate a victim, they pounce on top of it and inject venom that turns the snail’s insides to mush. Then the glowworm happily slurps up the goo like a snail-flavored shake.

As you can see, not every part of a firefly’s life sparkles.

Big Changes

Glowworms spend winter underground. Some species live for a year or longer as larvae. Others turn into adults when it warms up the following spring.

When a larva is ready to grow up, it digs a tiny chamber in the dirt or hangs upside down from a twig. Inside its body, glowworm body parts are broken down, rearranged, and put back together as shiny new adult body parts. About 10 days later, the metamorphosis is complete, and an adult firefly emerges.

You Glow, Girl!

The last two or three segments of a firefly’s abdomen — you might call it its behind — contain an organ called a lantern. Chemicals mix together inside the lantern to create light.

A firefly turns the light on and off with oxygen. When oxygen is added, the lantern blinks on. When oxygen is taken away, the lantern blinks off.

If you’ve ever touched a lit lightbulb, you know it gets hot. Ouch! But a firefly’s flashing fanny doesn’t make hardly any heat. This is for the best. If its behind got as hot as a lightbulb, a firefly would quickly turn into a crispy critter!

Different firefly species glow in different colors. Those that are active at sunset often glow yellow. Those that come out late at night tend to glow green. Some species even glow reddish-orange.

Love Songs with Light

Fireflies use their lanterns to talk to each other. And what they talk about on those warm summer evenings is romance. When a male flutters around in the dark, his twinkling tush acts like a neon sign. “Here I am,” it blinks. “Do you like me?”

Female fireflies don’t usually fly. Instead, they hide in the grass or perch on low-growing plants. When a female spots a male she likes, she blinks back. “Hey fella,” she blinks. “I fancy the way you’re flickering.”

This flashy chat can last for more than an hour until the lovesick male finally zeroes in on his soon-to-be girlfriend.

Dinner Date

Since different kinds of fireflies often live in the same place, males and females need a way to single out their own kind. That’s why each species lights up in its own special way. Some species blink slowly. Others blink quickly. Some blink in a pattern: twice in a row or three times. Big dipper fireflies, a common Missouri species, light up for a solid half second while flying in the shape of a “J.”

A few kinds of female fireflies imitate the flash pattern of other species. When a male shows up hoping for love, the female liar-fly grabs him and eats him for supper. Sometimes, love hurts.

Lights Out?

Biologists worry that some kinds of fireflies might soon blink off forever. In the U.S., one out of every three species may be at risk for going extinct. Here’s what you can do to keep the light show alive.

Let the grass grow.

Allow parts of your lawn to grow tall and give your rake a break. Tall grass and leaf litter keeps the soil soggy, which makes better habitat for baby fireflies.

Turn off lights.

Bright lights make it hard for fireflies to see each other twinkle. Turn on outdoor lights only when you need them and keep curtains closed in your house at night.

Avoid pesticides.

Most pesticides are deadly to beetles, including fireflies. Pesticides also kill snails and worms that baby fireflies eat. Ask your parents to avoid using them.

Help track fireflies.

Biologists want to learn more about which kinds of fireflies live where. You can help by joining the Firefly Atlas effort at fireflyatlas.org.

Also In This Issue

Animals have adaptations to help them catch food, avoid being eaten, and survive nature’s unforgiving environments.

And More...

This Issue's Staff

Photographer – Noppadol Paothong

Photographer – David Stonner

Designer – Marci Porter

Art Director – Cliff White

Editor – Matt Seek

Subscriptions – Marcia Hale

Magazine Manager – Stephanie Thurber