Missouri has six species of ashes that you might find in natural settings. They have been very popular as shade trees, and their hard, strong, shock-resistant wood is famously useful. Ash trees of all the species in North America are currently being killed by the invasive, nonnative emerald ash borer.

Ash trees in Missouri are usually dioecious, with each tree bearing either male (staminate) flowers or female (pistillate) flowers, but usually not both, meaning that a tree will produce either pollen or fruits, but not both. Note that certain trees may produce some perfect flowers (flowers that contain both pistils and stamens); some trees may change gender, or bear mixed flowers, from one season to the next; and blue ash bears mostly perfect flowers.

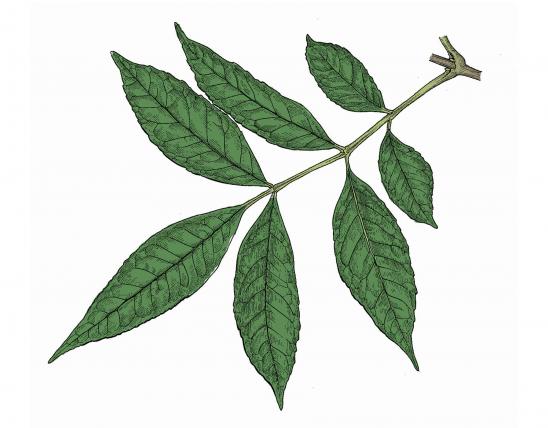

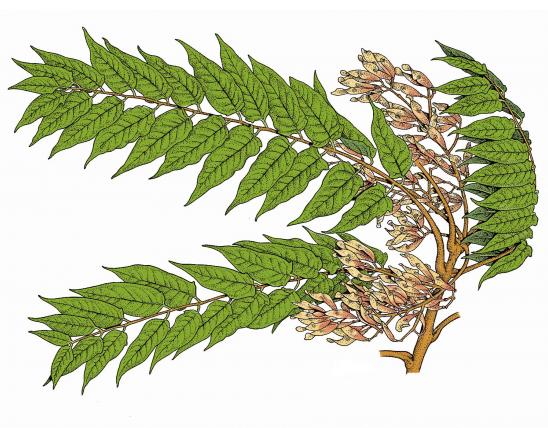

Ash leaves are opposite, pinnately compound with mostly 5–11 leaflets. Leaflets are mostly short-stalked, variously shaped, angled or tapered to the sharply pointed tip, rounded or angles at the sometimes asymmetric base, the margins entire or shallowly toothed, the surfaces smooth or hairy, the upper surface medium to dark green, the lower surface pale or lighter green.

Ash flowers are usually either male or female, with the two on separate trees. They form in the leaf axils in many-flowered clusters and are usually yellowish green or sometimes reddish. Flowers develop on one-year-old branches before the leaves or as the leaves are expanding in spring. The flowers are not fragrant or showy. Male (staminate) flowers produce copious amounts of pollen and can be a source of hay fever.

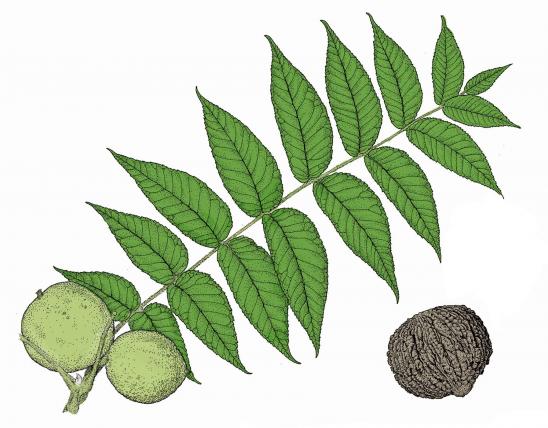

Ash fruits are samaras (like elms and maples, where the nutlet is enclosed in a flattened, papery wing). In ashes, the samaras are slender and elongated, oarlike, usually dangling in a cluster, 1–3 inches long (including the wing), the wing extending fairly straight out from the nutlet; pale green, turning straw-colored to grayish tan or brown with age.

The bark is gray, relatively thick, developing a network of ridges and diamond-shaped furrows, often described as X shapes, sometimes becoming scaly with age.

The twigs are relatively stout, gray to brown, more or less circular (though blue ash is 4-angled) in cross section, with raised leaf scars. The terminal buds are usually closely flanked by the uppermost, shorter pair of axillary buds, with several overlapping, sharply pointed scales. The bud shape and bud-scar shape varies and is useful for species ID.

Experts identify ashes to species by examining details of the twigs, including the shape of the leaf-bud scars, the fruits (length and width of the wings), and various characteristics of the leaves.

There are some 60 to 65 species of ashes worldwide. Six are native to Missouri.

- Green ash (F. pennsylvanica), also called red ash, is common statewide in a wide variety of habitats. Compared to white ash, it is more strongly associated with bottomlands and moister soils. Its leaflets are narrower than white ash’s; they turn bright yellow in autumn. This is one of the most widely planted shade trees around homes and along streets. In the wild, it lives along streams and in low grounds. Sadly, it is one of the trees most vulnerable to the emerald ash borer.

- White ash (F. americana) is common statewide in a wide variety of habitats. It tends to prefer somewhat drier or upland sites than green ash. Its leaflets are more egg-shaped than green ash’s, and they turn yellowish and deep, winey purple in fall, which is one reason it has been a popular landscaping tree. In the past, Sullivan’s ash and Biltmore ash were both considered forms of white ash, but genetic studies have shown that, in addition to the subtle differences in form, the three trees have different numbers of chromosomes, which prevents them from interbreeding, even when they occur nearby one another.

- Blue ash (F. quandrangulata) is scattered to common in the Ozarks and Ozark border and northward locally in the eastern half of northern Missouri. It is primarily an upland species, growing on glades, ledges and tops of bluffs, but also sometimes on banks of streams and rivers, bases of bluffs, and bottomland forests, often on calcareous substrates. It is one of our shorter ashes. This Missouri ash is identified by its twigs, which are strongly four-angled (square) in cross-section, the angles sometimes with narrow, corky wings. The flowers are usually perfect (having both male and female structures), and the fruits are wide (6–12 mm, as opposed to 3–8 mm in most of our other species), looking more oval and less like boat paddles.

- Pumpkin ash (F. profunda), also called red ash, is uncommon in Missouri, restricted to the Bootheel lowlands, where it lives in swamps, bottomland forests, and (uncommonly) in acid seeps; it may also be found on wet roadsides. It grows alongside bald cypress, water elm, and water tupelo. It has the largest leaves and fruits of all Missouri ashes but strongly resembles green ash. The wing of the fruits is 7–13 mm wide. It’s called pumpkin ash because of the swollen base of the trunk, which commonly develops at sites that are flooded for long periods of time.

- Sullivan’s ash (F. smallii) is scattered in the southern half in Missouri, where it grows in a wide variety of habitats, particularly in bottomland or streamside habitats but also in pastures, roadsides, and upland forests. Some botanists have considered it and Biltmore ash forms of white ash. Both are distinguished from white ash by the shape of the leaf scars (more shallowly notched than those of white ash), the color of the winter buds (brown, never black), and longer/larger samaras. Biltmore ash can be distinguished from the very similar Sullivan’s ash by its twigs and leaf stems, which are moderately to densely short-hairy, while the twigs and leaf stems of Sullivan’s ash are glabrous (smooth and hairless). Chromosome studies have shown that Sullivan’s ash is a tetraploid species (having four sets of chromosomes) while white ash is diploid (having two sets of chromosomes).

- Biltmore ash (F. biltmoreana) is uncommon in Missouri, known only from counties of southeastern Missouri, where it has been found in swamps and bottomland forests; its greater range is to the east of our state. Some botanists have considered it and Sullivan’s ash forms of white ash. Both are distinguished from white ash by the shape of the leaf scars, the color of the winter buds (brown, never black), and longer samaras. Biltmore ash can be distinguished from the very similar Sullivan’s ash by its twigs and leaf stems, which are moderately to densely short-hairy, while the twigs and leaf stems of Sullivan’s ash are glabrous (smooth and hairless). Chromosome studies have shown that Biltmore ash is a hexaploid species (having six sets of chromosomes) while white ash is diploid (having two sets of chromosomes).

Similar species: Many native trees have pinnately compound leaves. It helps to remember that ash leaves are opposite, not alternate. Another hint is that unlike trees like hickories and black walnut, the leaves of ashes, when crushed, do not have a spicy or strong fragrance.

- Common prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum) is a thicket-forming shrub or small tree. Its compound leaves resemble of those of ash trees, but it’s in a different family. Pairs of stout, curved prickles occur at each node.

- Mountain-ashes, or rowans (Sorbus spp.) are members of the rose family. The leaves look a little like those of ashes, but the fruits are very different; the fruits are tiny pomes (apples).

- Flowering ash, also called manna ash (Fraxinus ornus), is native to Eurasia and is sometimes planted in Missouri for its large, terminal clusters of fragrant flowers with slender, white petals. It is not known to escape from cultivation, however.

Height: Pumpkin ash is our tallest species, growing to 130 feet tall. Biltmore ash reaches 115 feet. White ash reaches 100 feet. Green ash and Sullivan’s ash both reach about 80 feet. Blue ash can possibly reach about 100 feet tall, but it is usually much shorter as it mostly grows in challenging, dry blufftop habitats

Statewide. Different species have different habitat preferences and therefore different regional distributions

Habitat and Conservation

Ashes are common components of most upland and bottomland woodland and forest communities. Each has its own most common habitats, but most species are capable of living in a range of habitats. Ashes, especially white and green ash, have been very popular as ornamental, shade, and street trees. Green ash has been more commonly cultivated because of its faster growth.

Green ash’s popularity as a street tree and shade tree soared after Dutch elm disease killed off most of the big elms that had been cultivated in yards and parks and along streets. Green ash was viewed as the new favorite to replace the elms. Unfortunately, Americans are now faced with another devastating tree-pandemic, as all of North America’s native ash trees are seriously threatened by the spread of the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis, or EAB).

The grublike larvae of the emerald ash borer feed on the inner bark of ash trees, disrupting the tree’s ability to transport water and nutrients, ultimately killing the tree. This nonnative, invasive insect probably arrived in the United States on solid wood packing material carried in cargo ships or airplanes originating in its native Asia. As of about 2020, the insect has spread from the east coast all the way west to Manitoba, South Dakota, Colorado, and Texas.

Insecticide options exist for protecting individual ash trees from EAB infestations, but these professionally applied treatments can be expensive. Most people will probably opt to replace their dying ashes with some other kind of tree.

On another front, efforts are under way to develop biological controls — mainly other insects and fungi that might parasitize the emerald ash borer and keep its numbers to a nonlethal level.

Finally, ash species that are resistant to EAB are being sought and studied. Not surprisingly, ash species native to Asia (where they have long coexisted with the EAB) are most resistant to the insect. Gene sequencing research is locating the genes involved with EAB resistance, and, using gene editing, it may be possible to incorporate these genes into North American and European ash species that are otherwise completely vulnerable and dying from the insect.

Status

All of North America’s native ash trees are seriously threatened by the spread of the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis). Since its discovery in North America, the insect has killed hundreds of millions of ash trees on our continent and has cost cities, property owners, nursery operators, and forest products industries hundreds of millions of dollars.

Biltmore ash is listed as a Missouri species of conservation concern, ranked “SU,” which means “species unrankable,” due to lack of information or due to substantially conflicting information about status or trends.

Human Connections

The wood of ashes is commercially important for its great strength and shock resistance. It is used in furniture, flooring, veneers, baseball bats, hockey sticks, canoe paddles, a wide range of implement handles, and handcrafts. White ash is particularly beloved for baseball bats. It is the original favorite of big-league players, offering lightness, flexibility, and a lower percentage of multi-piece fractures should the bat be broken from big-league-level swings.

Native Americans historically used various parts of ash plants medicinally, ceremonially, and as a minor food source.

For as long as anyone can remember, Native Americans in the northeastern United States and eastern Canada have used black ash (F. nigra) for making baskets. It has the special property of not having the growth rings connected by fibers, making it perfect to break into tough, flexible strips for basketry. The potential loss of this species could spell the loss of this art form.

Blue ash got its name because early pioneers took strips of the inner bark or branches, mashed them in water, and made a blue die.

The windborne pollen of ashes can be a major component of spring hay fever.

Ashes have long been valued as shade, park, and street trees that turn beautiful colors in the fall: yellows in green ash, and yellow and purple in white ash. In our fall color landscapes, we will especially miss the unique, rich plum-reddish-purple color of white ash in the years to come.

The emerald ash borer has caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage. Homeowners must pay to have large trees removed; unremoved dead and dying trees are more likely to topple in storms and cause damage to property and cause power outages. White ash, a longtime favorite wood for baseball bats, is becoming scarcer. Cities, which had widely planted green ash along streets to replace the many elms that died of Dutch elm disease, are having to cut down ashes and decide what kinds of trees to plant next. Urban foresters are now recommending that tree plantings should be diversified — using a wide variety of tree types, instead of relying only on a few species — which can help prevent widespread damage should a new invasive pest appear.

Sullivan’s ash is named for Fr. James Sullivan, a dedicated amateur natural historian who, many years ago, noticed that true white ash has buds that are darker brown or black, and tend to be more sunken into the twigs, than in the species now called F. smallii. Members of Missouri’s Webster Groves Nature Study Society were the first to suggest the species be called Sullivan’s ash.

The emerald ash borer did not spread to North America by itself; it was introduced here by humans, apparently hidden in the wood of pallets, shipping containers, or other wood shipped here from its native continent. Its spread within North America has been expedited by people transporting infested ash saplings and firewood into areas where the insect was not present before. You should never move firewood from one locale to another; burn it where you got it.

Ecosystem Connections

A variety of birds and rodents eat the seeds of ashes, including cardinals, finches, bobwhites, wild turkey, mice, and squirrels. The seeds of pumpkin ash, which often lives in swampy areas, are eaten by ducks.

Where they grow near water, ash trees (especially green and pumpkin ash) may be used by beaver in building their lodges. Beaver also eat the twigs, bark and wood.

Numerous insects feed on the leaves, fruits, wood, or sap of ashes, including a wide variety of aphids, scale insects, plant bugs, weevil larvae, bark beetle larvae, longhorned beetle larvae, leaf beetles, gall fly larvae, sawfly larvae, and more.

The red-headed ash borer (Neoclytus acuminatus) is a native longhorned beetle whose larvae feed on a variety of dead or dying hardwood trees, including ash. They enhance the decomposition process but are not usually a cause of tree death.

Certain types of woolly aphids and scale insects are common on ash trees, and these aphids fall prey to one of the world’s very few carnivorous butterfly species, the harvester (Feniseca tarquinius; it’s in the same family as blues, hairstreaks, and coppers). The female harvester deposits eggs near a colony of the aphids, and the caterpillars prey on the aphids.

The caterpillars of many kinds of butterflies and moths eat the foliage of ash trees. Some species you might be familiar with include:

- Eastern tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus)

- Hickory hairstreak (Satyrium caryaevorum)

- Mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa)

- American dagger moth (Acronicta americana), and many other noctuids (daggers, underwings, sallows, etc.)

- Ash borer or lilac borer moth (Podosesia syringae)

- Banded tussock moth (Halysidota tessellaris)

- Carpenter moth (Prionoxystus robiniae)

- Cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia)

- Eastern tent caterpillar (Malacosoma americana)

- Faint-spotted palthis (Palthis angularis)

- Fall webworm (Hyphantria cunea)

- Great ash sphinx (Sphinx chersis)

- Hag moth (Phobetron pithecium), whose larvae are the weird-looking monkey slug caterpillars, with stinging hairs

- Harris’s three-spot (Harrisimemna trisignata)

- Io moth (Automeris io)

- The maple spanworm, or notch-winged geometer (Ennomos magnaria), and several other geometrid moths

- Polyphemus moth (Antheraea polyphemus)

- Regal moth (Citheronia regalis)

- Reticulated fruitworm (Cenopis reticulatana), just one of many tortricid moths that eat ashes

- Virginia tiger moth (Spilosoma virginica), whose larvae are the familiar “yellow bear” woolly bears

- Walnut caterpillar moth (Datana integerrima), and several other prominent moths

- Waved sphinx (Ceratomia undulosa)

- White-marked tussock moth (Orgyia leucostigma), whose larvae are covered with distinctive groups of hair tufts, some long, some short; the hollow, barbed hairs can sting if you brush against them.

Keep in mind that most birds — even ones that eat seeds and berries at other times of the year — require insects during nesting time, for the added protein. Trees are part of an ecosystem; a tree that feeds insects indirectly feeds the birds.

Woodpeckers like to eat the larvae of wood-boring beetles, including the emerald ash borer; one sign of an EAB infestation can be heavy woodpecker damage on ash trees.

Ashes, like other trees, have their own suite of fungi. The fungus that causes ash heart rot, Perenniporia fraxinophila, is parasitic on ashes, frequently causing death. The edible ash tree bolete (Boletinellus merulioides) grows scattered on the ground near ash trees and is associated with an insect aptly called the leafcurl ash aphid. Morels are associated with ashes, too (in addition to elms, apple trees, and several other species); their fungal networks connect with the roots of trees in a mutualistic relationship. When you are hunting morels in spring, make sure to look under dying ash trees.

Like other trees, ashes offer habitat and shelter to a variety of animals. Spiders creep along the bark, insects overwinter in bark crevices, birds and squirrels rest and nest in the branches, and woodpeckers, bluebirds, owls, wood ducks, tree squirrels, and bats may live in cavities in older trees.

Botanical relatives of ashes: Some commonly cultivated nonnative shrubs and trees are in the same family as ashes (the olive family), including Persian lilac (Pontanesia phillyreoides) and common lilac (Syringa vulgaris), various species of Forsythia, jasmines or jessamines (Jasminum spp.), and privets (Ligustrum spp.). Several of these can escape from cultivation and form self-sustaining colonies. Sometimes, you can encounter old lilacs, privets, forsythias, or other landscaping shrubs persisting at old home sites long after the house they adorned has disappeared. European olive (Olea europaea) is the species that produces the well-known edible fruits and olive oil; it is grown as an ornamental in warmer climates, but it does not survive Missouri’s winters.